Why Canada's election system is bad, and why it matters

A straightforward introduction to electoral reform in Canada.

‘Kitchen table issues’ is a term that gets thrown around often during political campaigns in North America. It refers to an undefined set of primarily economic issues that have a direct impact on the lives of ordinary people on a day-to-day basis. It’s self-evident why campaigning on issues like cost-of-living, health care and housing can grab peoples’ attention. These might also be referred to as ‘bread-and-butter’ or ‘pocketbook’ issues.

Electoral reform, on the other hand, is definitely not a ‘kitchen table’ issue. People often don’t see the value in spending time agonizing over something like electoral reform when rent is due on the first of the month. At the same time, this issue has a tremendous impact on our society. It determines who controls the government, and who is writing legislation. It determines who is making decisions about the economy, and all of those other ‘kitchen table’ issues. Let’s examine Canada’s electoral system a little bit, because I want to show you why it matters.

How does Canada’s election system work?

Canada uses an election system called First-Past-the-Post (FPTP). The way that this system works is by dividing the country into hundreds of electoral districts. In each district, each political party can run one candidate. Each voter will cast a ballot with which they select one candidate whom they prefer in their district. The single candidate who receives the most votes in each district is elected, and will become a Member of Parliament (MP). The party that elects the most MPs will usually form government, and if the largest party does not have the support of a majority of MPs, they must rely on opposition parties to support them.

In the last federal election in 2021, candidates representing the Liberal Party of Canada were elected in 160 districts, candidates representing the Conservative Party were elected in 119 districts, and so on.

An administration will survive as long as it enjoys the confidence of more than half of the House of Commons, whether they are government or opposition MPs. For the last three elections, a majority of the House is 170 MPs. Since 2019, the governing Liberal Party has been relying on MPs representing the opposition New Democratic Party to support their government.

While it has no impact on formation of government, we can also consider the popular vote. The popular vote refers to the total number of votes that were cast for candidates representing each party across the entire country. Here’s what the popular vote looked like in each province in 2021.

First-Past-the-Post (FPTP) is what is known as a winner-take-all (or ‘majoritarian’) electoral system. It’s a system where the winners are based on which party receives the largest share (or the ‘plurality’) of the vote, rather than a system which aims to take all voters into consideration. With that in mind, let’s examine some of the problems that our election system causes.

False majority governments

The most glaring issue with the FPTP system is that it can deliver majority governments to political parties which have failed to earn the support of a majority of voters. All that a party needs to form the government in Canada is the confidence of a majority of elected representatives. However, because MPs are elected only based on the condition that they received the largest share of the vote in their district, that can lead to distorted results.

In the 2015 Federal Election, the Liberal Party was elected to a majority government, with 184 seats out of 338 (54%). However, they only got the support of 39% of voters. That means there is a disparity of 15% between the government’s share of the legislature and their share of the vote. It should be noted that this is not an exception. This is the case in 7 out of 10 provinces, all ten of which are currently governed by majority governments.

That means that, in 7 out of 10 provinces, opposition parties represent a larger share of the electorate than the government does. While the most popular party usually (not always) forms the government in FPTP elections, this kind of disparity between the popular vote and the government can leave a lot of people unhappy.

Two-party politics

The only parties that have ever formed government on a federal level in Canada are the Liberal Party and the Conservative Party (or its direct predecessors). That is not to say that third parties are not a factor in Canadian politics. However, the office of the Prime Minister of Canada has long been either red or blue.

Canada’s electoral system solidifies two-party rule. Under plurality systems like FPTP, voters are usually hesitant to support smaller parties, because they fear ‘wasting’ their vote on a party that is unlikely to win. This hesitation usually pushes them to support one of the two largest parties. The mechanics of the system create massive barriers for smaller political parties, which restricts them from securing any kind of representation, even with hundreds of thousands of votes across the country. What I am describing here is Duverger’s law, which was formulated in the 1960s by French political scientist Maurice Duverger. The law holds that plurality systems like FPTP foster a two-party system by virtue of the way that the rules compel voters and candidates to behave.

Regional disparities

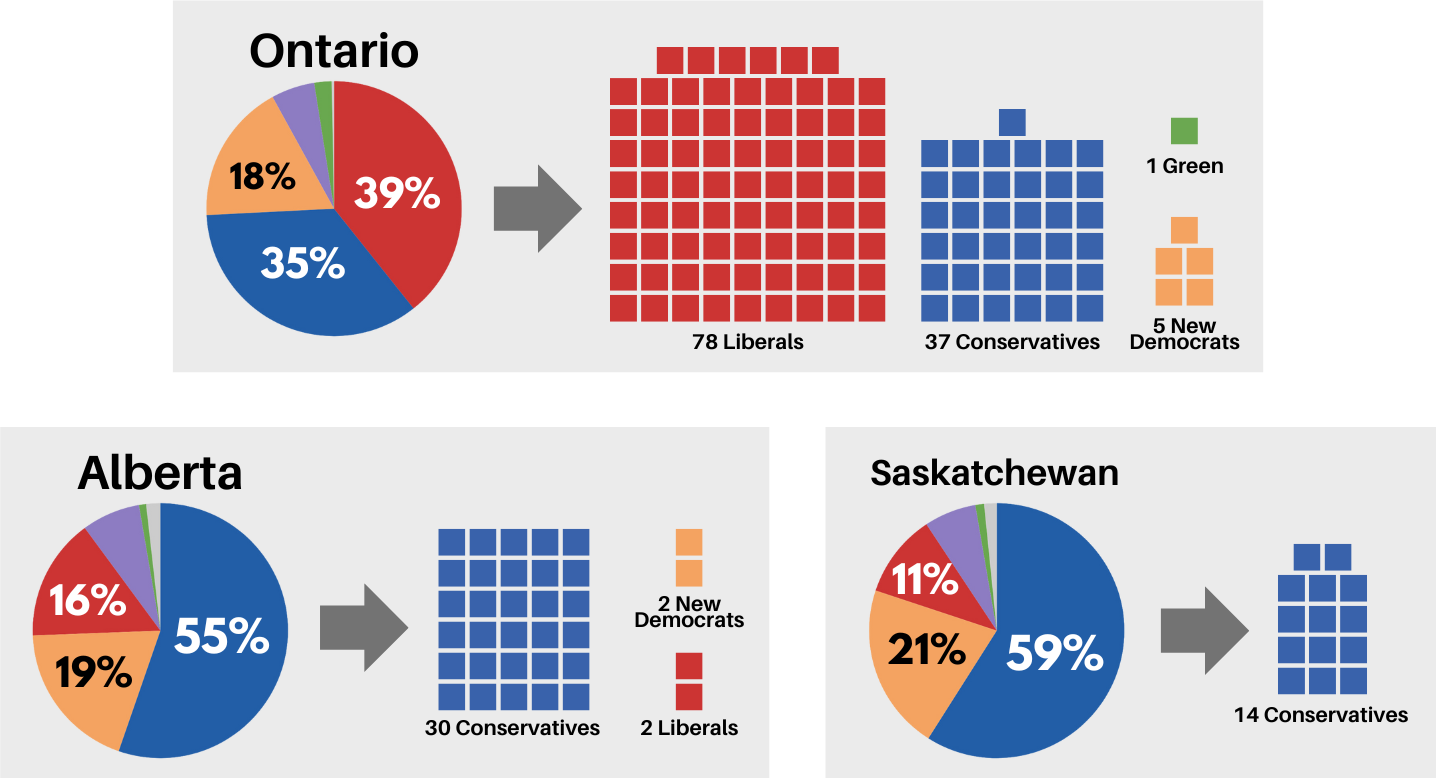

For a country like Canada, this is one of the most dire flaws of our election system. Let’s compare the popular vote to the number of MPs elected in the provinces of Ontario, Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Both historically and at present, the Liberals enjoy stronger results in the east, while the Conservatives enjoy greater success in the west. However, looking at this distribution, this difference is exaggerated to absurd proportions.

Between the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan, only two Liberal MPs were elected. This is despite candidates representing the Liberal Party earning over 350,000 votes (that’s more than the total number of votes cast for all candidates in Newfoundland and Labrador). In fact, Saskatchewan hasn’t elected a Liberal MP since 2015, meaning that the province has been completely excluded from the government for the last five years. Looking at Ontario, the Liberals and Conservatives received a similar number of votes, about 2.5 million for the Liberals and 2.25 million for the Conservatives. But there are more than twice as many Liberal MPs representing Ontario than Conservative MPs.

Not only can this kind of poor representation cause entire provinces to be shut out from the government, but it also propels the skewed perception that we as a country are far more politically divided along provincial lines than we actually are, which enables politicians to engage in very divisive rhetoric.

How do we fix this?

As mentioned before, First-Past-the-Post is a plurality-based, winner-take-all electoral system. To address the problems I outlined in this post, we must adopt a system which uses Proportional Representation (PR). Electoral systems which use PR are the most common in the world, including almost all democracies in Europe and Latin America. Proportional election systems are designed to take into consideration all voters, which generally results in a trend away from a two-party system and towards a healthier, multi-partisan democracy.

There are many different types of PR-based election systems, but the two which are most commonly proposed for Canada are Mixed-Member Proportional Representation (MMPR, used in Germany and New Zealand) and Single Transferable Vote (PR-STV, which is used in Ireland). When someone says ‘proportional representation,’ it doesn’t refer to one specific election system in the same way that saying ‘FPTP’ does. There are a multitude of PR-based election systems that all have different features and parameters.

The diagram below shows how the popular vote translates into elected representatives in proportional election systems (Germany, Ireland) compared to winner-take-all systems (Canada, United Kingdom). Note the extent to which the political power of large parties is exaggerated in the results of the Canadian and UK elections.

This side by side comparison also makes it much more obvious that FPTP pushes voters into a two-party system. PR makes it much more difficult for a single party to govern alone, which forces them to compromise with other elected officials, and therefore create governments that are more representative of the population as a whole.

How do we get there? It’s like any other piece of legislation in Canada. The proportional representation advocacy organization Fair Vote Canada proposes that the next step is for Canada to host a National Citizens’ Assembly on Electoral Reform, which would allow us to come to a proposal for a new election system without the interference of sitting MPs.

Why does it really matter?

We are living in an era of faltering institutional legitimacy. As a result of the perceived failure of our institutions to effectively address problems from cost-of-living to climate change to global peace, people are becoming disenfranchised or turning to radical/reactionary ideologies. If you believe that these institutions must continue to stand, then that requires an answer to those challenges towards legitimacy, which can come in many forms.

Changing the Canadian election system, from the current FPTP system to a system of proportional representation, would help our governments reclaim some institutional legitimacy. By ensuring that the parliament of Canada, and by extension of the government of Canada, is more representative of Canadian voters as a whole, it would bridge the disconnect between Canadians and their elected representatives. It’s not magic, and more would have to be done, but it’s an important step to actually solving these problems.

This is all to say, electoral reform is something that must end up on the agenda. It is not a kitchen table issue, and it is unlikely to ever become an eye-catching issue. However, sometimes the necessary work is neither glamorous nor interesting. Our elected representatives must find the courage to fix Canada’s broken democracy.