Are landslide elections good for democracy?

A representative opposition is just as important as a representative government.

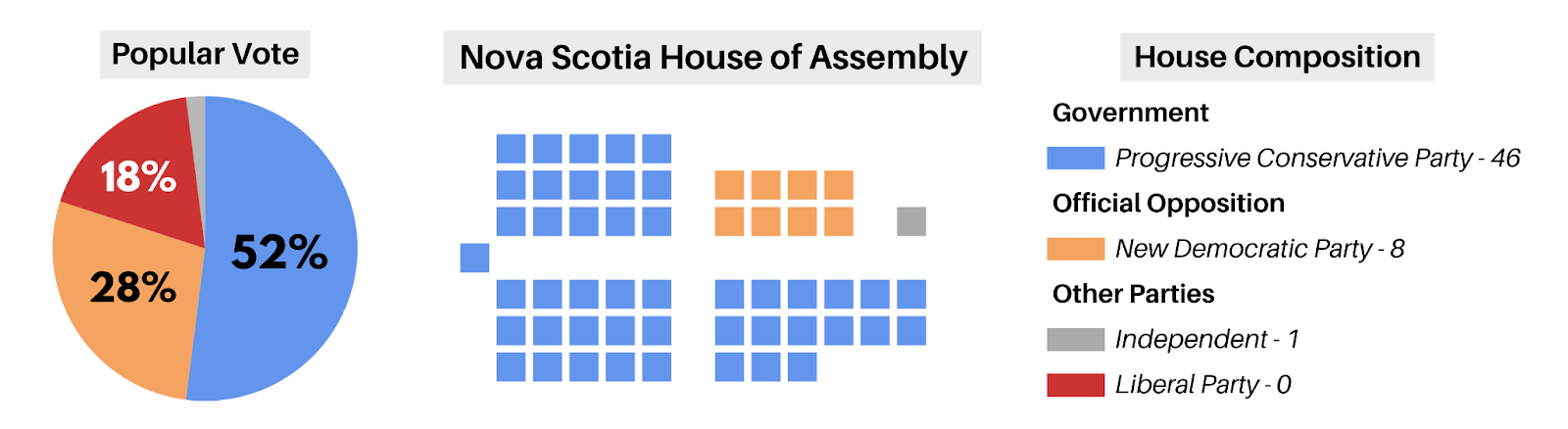

On November 26th, voters in Nova Scotia will go to the polls for a provincial election, called by the Progressive Conservative (PC) government led by Tim Houston. Based on all available polling, we can expect a substantial victory for the incumbent conservatives. At the time of this article’s publishing, polling analyst Philippe J. Fournier’s model for the election, 338Canada, suggests that the Nova Scotia PCs could win as many as 46 seats with up to 52% of the popular vote. That means that a staggering 84% of members of the legislative assembly (MLAs) would be members of the governing party.

Of course, nothing is set until election day. But let’s say that the PCs have a stronger than expected result, and the Liberals underperform. In that case, we could see a legislature that looks something like this:

Nova Scotia is facing the realistic possibility that government MLAs could outnumber the opposition at a ratio of 5-to-1. There is value in examining whether that will be good or bad for the province, bearing in mind the role that opposition parties typically play in Canadian parliaments. Given that, even in this 46-seat landslide scenario, 48% of Nova Scotia voters would still have chosen to support opposition parties, we should ask the question: should these voters have more of a say in the composition of the legislature?

What does the opposition even do?

In the simplest terms, the role of the opposition is to challenge the government in its agenda, applying scrutiny and pressure to ensure that they are governing honestly and effectively. The relationship between the government and opposition is adversarial by design, and it places elected officials in a position where they can criticize and question the government without having their loyalty to the people of Canada called into question, by virtue of their status in the House of Commons.

Criticism is central to the role of the opposition, so much so that members of the opposition often organize themselves into a “shadow cabinet” composed of “critics.” Each opposition critic is assigned one or more portfolios that align with the responsibilities of a government minister, and their role is to scrutinize that minister’s activities. On a federal level, the Conservatives, New Democrats, and Bloc Québécois all have shadow cabinets, each filled with critics on numerous government portfolios. This practice also takes place at a provincial level. This system creates space in the legislature for a variety of perspectives and dissent about the government’s activities.

Opposition parties are also granted the right to organize the agenda of the legislature on opposition days, which provides them with an opportunity to set the topic of debate to something which the government might prefer to ignore. The largest opposition party, designated as the “Official Opposition” also enjoys some special privileges, including having the right to speak first after the government, and earning more time during Question Period than other opposition parties.

The role that the opposition plays is crucial. An elected opposition provides an official avenue for Canadians who are dissatisfied with their government to express that dissatisfaction, and in turn the elected officials themselves can utilize their privilege as members of their legislature to apply a level of informed scrutiny that someone outside of the legislature may not be able to. However, this all comes with the big caveat that the opposition can only be as effective as it is representative, and often the opposition is not very representative.

How common are landslide results?

For the purposes of this discussion, let’s define a landslide election result as the governing party getting at least three-quarters (75%) of the seats in the legislature. Let’s ignore the popular vote for now. At a provincial level, this kind of election result is fairly common.

Just looking at elections that have taken place since 1970, there have been 37 elections where the government would go on to hold at least 75% of the seats in the legislature. That means that one-in-four of the last 148 provincial elections held in Canada have created legislatures where the government outnumbered the opposition by a ratio of at least 3-to-1.

But now let's compare this to the popular vote during the same period. There has only been a handful of cases where a party has earned more than 60% of the popular vote. No party ever received more than 70% of the vote in a provincial election. Why then, should the opposition so often be relegated to such a small share of the legislature?

Look at the most recent election in Prince Edward Island. In 2023, the Green Party and Liberal Party together earned about 40% of the popular vote, but were relegated to only 19% of seats in the Legislature. There are similar cases from not too long ago. Take the 2001 British Columbia Provincial election, where the opposition consisted of 2 MLAs, who were expected to hold 77 government MLAs to account. Or the 2008 election in Alberta, where the government consisted of 72 MLAs, and the opposition of just 11 MLAs.

Then of course there’s the famous New Brunswick election of 1987, where Frank McKenna’s Liberals won a clean sweep, electing MLAs in all of the province's districts. This led to a situation where there was literally nobody in the legislature to hold the government to account. To ensure that parliament could still function, Premier McKenna selected a handful of members of his own party to form a sockpuppet opposition caucus, and allowed the runner-up Progressive Conservative Party to submit written questions to be read during Question Period. But that’s a little bit ridiculous, is it not? While the election was a landslide, the PCs earned nearly 30% of the popular vote, and the New Democrats earned over 10%. That should be enough of the popular vote for a party to earn some kind of representation in the legislature.

How can we elect more representative legislatures?

The idea that the legislature should reflect the will of the voters is not a radical idea. In Nova Scotia, the most likely outcome is a severe reduction in the number of opposition MLAs, down to as low as 16%, despite candidates for opposition parties still being likely to receive upwards of 45% of the popular vote. It will result in a legislature that is less representative and diverse, and one that makes it even easier for the government to bypass challenges from the opposition.

The reason that such unrepresentative election results are possible in Canada is because we use an election system called First-Past-the-Post. This system, which has fallen into disuse in most liberal democracies, functions in a way that cultivates two-party politics and creates election results that end up wholly unrepresentative of the collective will of the voters. Most countries make use of an election system built on a principle of proportional representation, which aims to ensure that all votes cast will contribute towards the election of a representative, rather than just votes towards the most popular parties. This helps ensure that both the government and opposition are representative of the entire electorate.

Reforming the election system is not a magical solution that will fix every problem in our political discourse. However, it would help remedy one of the key issues that seems to be cropping up in modern democracies; a perceived disconnection between voters and their representatives. If we create a system that allows voters to elect representatives who they believe are truly representative of their values, the most likely result is better outcomes for all Canadians.